Lawrence Hart

Poet, teacher, and critical maverick Lawrence Hart (1901–1996) was one of his century’s deepest and orneriest thinkers about the art. No uncritical booster, Hart rejected the bulk of the writing that goes by the name of poetry as just not exciting enough to warrant our attention. He sought to define exactly what going on in that small percentage of verse that makes the whole pursuit worthwhile.

Early life

Hart was born in 1901 near Delta, Colorado. As a young man he wandered around the West, accumulating the kind of experiences that would read well on a book jacket: organizing a revolt against compulsory military training at his high school in Santa Rosa, California; working as a roughneck on a southern California oil rig; canning fish in Alaska; beginning and abandoning a career as a newspaper reporter. Whatever else he was doing, he was reading poetry: not poems but poets, whole lifetimes of verse from the first line to the last. He marked and memorized the passages he liked best and began to ask himself why he chose them.

In the late 1920s, Hart settled in San Francisco. Seeking out artists and writers, he lived first on Telegraph Hill and later in the old “Monkey” Block at Montgomery and Kearney, a warren of studios that was the city’s informal artists’ colony. (The TransAmerica Pyramid stands there now.)

In the 1930s he got involved with the Barter Movement, a social experiment that arose in response to the economic hard times. Cold-shouldered by the New Deal as too radical, it was at the same time infiltrated by orthodox Communists, who sought to make it a front organization. It fell apart.

Hart was now writing verse of his own and getting some of it published. He wrote reviews and did some criticism for local writing circles. He also started a literary magazine, The Talisman, which lasted only two issues. Later on, when someone mentioned having a copy, he would ask to borrow it, and destroy it.

“This makes it go”

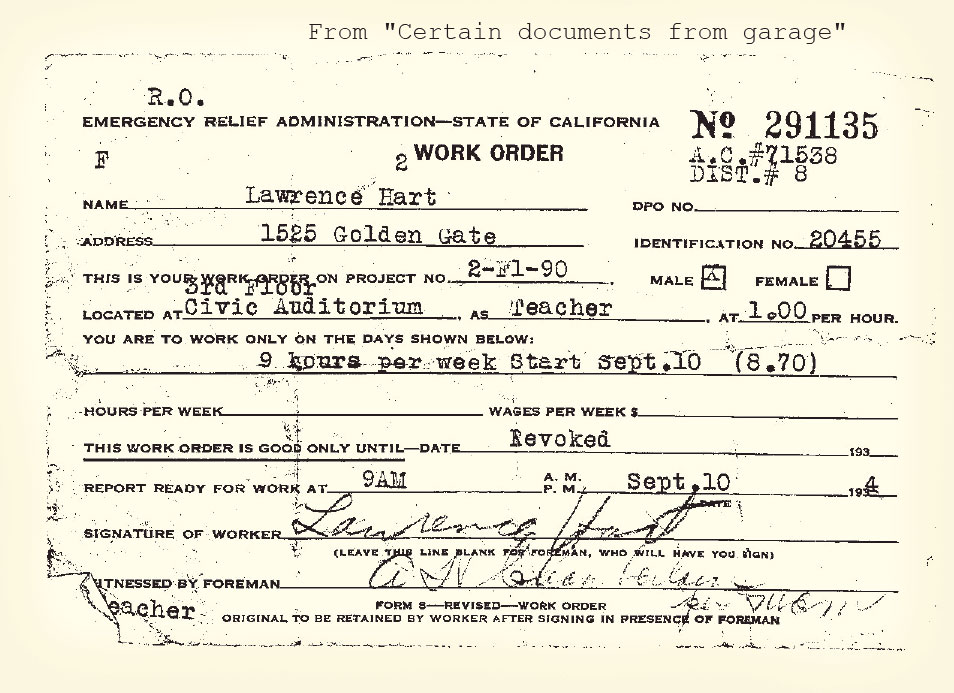

In 1934 he took a teaching post in the Emergency Education program, a New Deal venture designed to provide a bit of income for just about anybody who felt an urge to teach. He drummed up some students and began telling them how to write poetry.

Was he qualified? By his own account, not remotely.

Hart at this point was a stylistic conservative, blind to the innovations of his own time. But teaching transformed his opinions. Within a couple of years, he was a passionate advocate of literary Modernism. In poets like Auden, Dickinson, Eliot, Hopkins, MacLeish, Pound, and Yeats, he found a level of excitement—a skill and daring in the use of language—that exceeded almost anything in English since Milton. He sensed the same power in such European voices as Lorca, Perse, and Rilke. He felt he was witnessing an age of discovery. He decided he would be one of the discoverers.

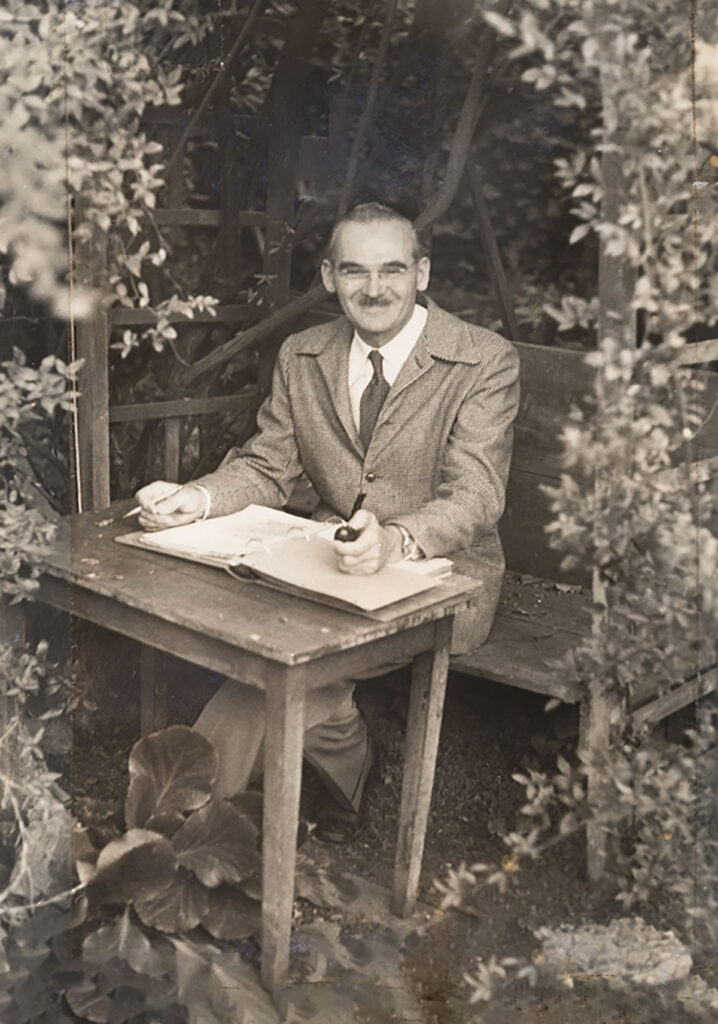

Hart’s genius was not as a poet—though he left a few fine sonnets—but as a passionate analyst. His method was to annotate poems, marking the passages that seemed to him to be carry the excitement; to type out what he had marked; and to study the resulting lists (thousands of pages in all) in the attempt to see what the writers were doing in these lines. When he thought he had identified a particular technique in use, he would describe it and ask his students to try the same. Their own new work would then undergo the same selection and study.

The Modernist poets liked to talk about technique rather than “inspiration.” Hart took this attitude as far, perhaps, as anyone has. Though he acknowledged the role of the unconscious, and sought ways to enlist its aid, he had no patience with the idea that certain poetic effects are inexplicable, ineffable. If some group of words stands out, leaps up, impresses itself on our minds, there is a reason.

His student Rosalie Moore would capture something of his approach:

You, Lawrence Hart, had better carry a crux-bug,

jump-bob, tick-nut:

Wind up the palm to show—

Say This makes it go.

The long career

For fifty-five years Hart was constantly teaching somewhere in the San Francisco area: at the University of California Extension, at Mills College, at the two-year College of Marin, in special children’s classes in junior high and high schools. But he never had more than one foot in the academic world. The heart of his work was in private seminars to which he invited the most promising of his students. These workshops continue to this day.

In 1944, Hart married Jeanne McGahey, a poet he met in his classes, and moved to Berkeley, where their son John was born in 1948. In 1951, the family crossed another bridge to settle in San Rafael in what was then rural Marin County, home base for the rest of the century.

From that vantage point he observed a changing poetic landscape. He saw the fading days of Modernism and the triumph of the “New American Poetry,” based on repudiation of the models Hart valued most. For him, this was not a step forward but a kind of counter-revolution: a pell-mell retreat, a turn away from adventure in poetry and back to something tamer and more obvious. Unimpressed and unabashed, he continuing his own explorations, refining his analysis, trying out various teaching methods, and speaking out at every opportunity against emerging norms.

It seems that we’ll never be permitted to graduate from the university of the obvious.

—Art critic PETER SCHJELDAH

Alongside his classes for adults he gained a lot of press for his work with children and young adults. He insisted that youngsters, whether or not labeled “gifted,” could benefit by learning some of the tools of quality writing—skipping over the step of the correct but boring school paper.

Forthcoming

Lawrence Hart never finished the comprehensive Poetics he left in a myriad drafts under various titles. In the middle 1980s, however, Hart and McGahey brought out a tabloid newsletter of literary debate, called the poetry LETTER—a kind of web forum before the Web. Along with some entertainingly sharp exchanges, the LETTER captured a number of key statements by its editors. The Lawrence Hart Institute—created at this time as the recipient of grant money—will soon publish a selection of these and earlier statements now scattered among diverse publications.

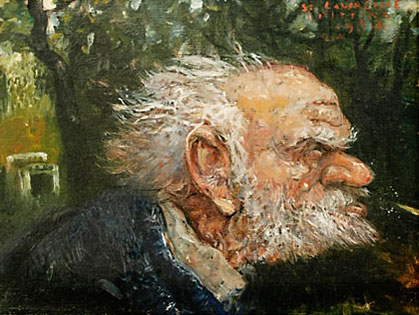

[Gallery of more LH photos forthcoming]