The Activist Idea

Two things are true. Poetry is wonderful; and the bulk of the writing that goes by that time isn’t wonderful at all. Much of it is nice but no big deal. Much of it is lineated prose that might read better if presented as such. And much of it is just plain dull.

We have always known this, in a way. John Dryden prized his “hits,” the lucky moments in his poems that seemed to exceed his conscious skills. The nineteenth century spoke of “felicities” in poetry, quietly acknowledging that these high points are rare. The expectation that poems over sonnet length should be poetically moving—from the first line to the last—just wasn’t there.

This wish for the thing to be integrated by its intensity seems to be fundamental, although it might be wise to allow for the possibility that it has taken the whole of historic time for the wish to become so clear to us. We tend to deduce that even a poem that is laid out like an essay is trying to be a short poem. It just might not have the wherewithal.

—Critic CLIVE JAMES

Early in the 20th century, the poets known as the Modernists raised the stakes. They challenged each other to build poems, short or long, that were stimulating and original from one end to the other. When Ezra Pound described Eliot’s Waste Land as “the longest poem in the English language,” he wasn’t counting lines: he was praising sustained intensity. This measuring stick was new.

Ten years after Pound wrote that praise, Lawrence Hart was taking up the cause of intensity, or, as he called it, the active element in poetry—from which the label Activist would arise.

Four principles

Hart’s approach was based on four ideas, each of which an ancient pedigree, each of which he extended well beyond prior models, and each of which, in today’s poetic climate, is something of a heresy.

1. The key to poetic force is surprise. Strength comes from the unfamiliar, out-of-context, even seemingly wrong expression or word-arrangement that after all turns out to be right and meaningful. The greater the disturbing element or “discord,” the greater the pleasure that comes with the recognition of rightness or “accord,” and the stronger the overall effect. New readers of poetry may shy away from unfamiliar elements at first, but will gain a deeper pleasure if they persevere.

2. Poetry need not make obvious “sense.” The art works by impression and association—what the Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce called “connotation”—and not essentially by literal meaning, or “denotation.” Following Croce, Hart posited a whole world of intuitive knowledge parallel to and no less valid than the world of factual information. Poetry moves in this parallel world. A good poem must hang together as an intuited pattern, a word experience. It may also allow itself to be translated quickly into a prose idea—or not.

3. Many of the techniques that make good poetry can be taught. The varied skills that poets have worked out for themselves over the ages—often without consciously defining them—can be described, isolated, mastered, and extended. This is not a matter of “rules” but of tools, to be applied in changing, individual ways.

4. The single line or image is the place to start. Hart saw two routes to the successful poem. In the ancient and always more common procedure, the poet builds poems, so to speak, from the outside in, filling out a plan or following a series of impulses. Really striking passages may (or may not) emerge of themselves along the way, or be shaped in revision. “It is possible for a writer to begin with something very much like prose and to lift this material into poetry,” Hart acknowledged.

He offered, however, a second approach: “to begin instead with brilliant if fragmentary poetic detail, and [then] work toward order and clarity.” He thought this progression from small effects to large, though difficult enough, was the surer route toward the heights, and one useful to more people.

Hart’s curriculum

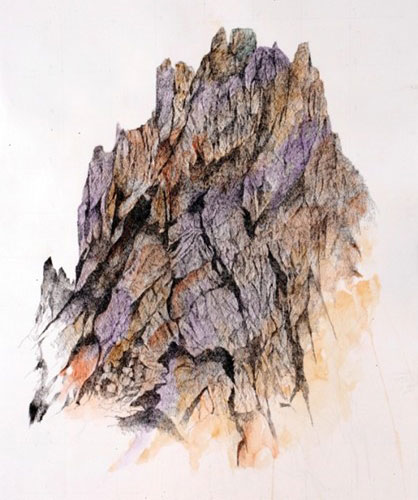

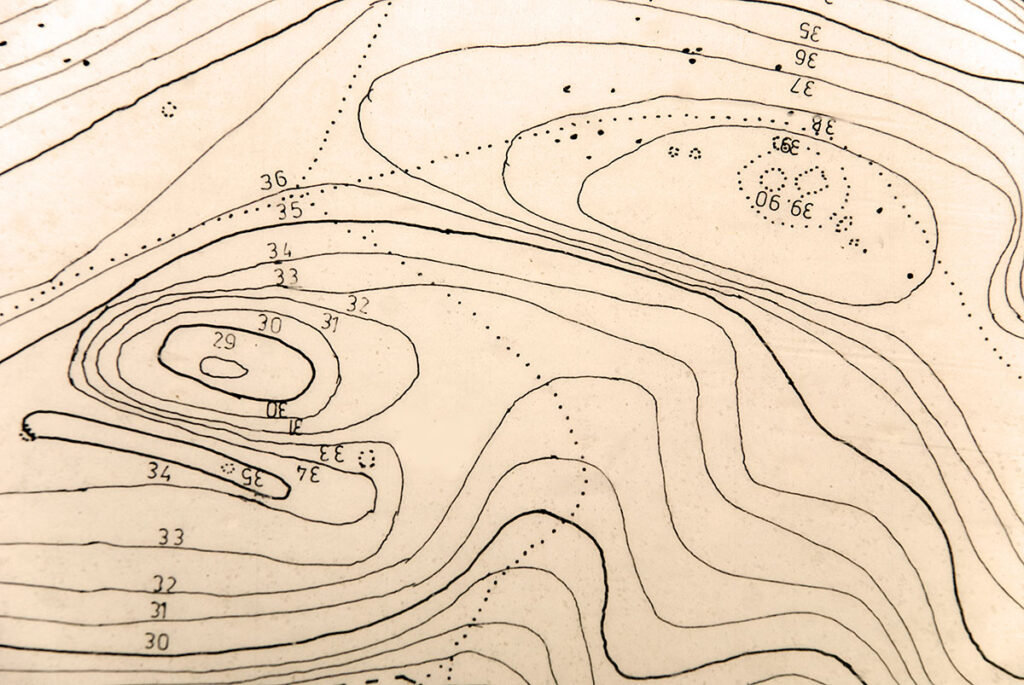

Putting these ideas into practice, he developed a sequence of basic assignments that remains the core of the method today. It began with a type of severely disciplined descriptive writing, free of all comparison and generalization, which he called Direct Sensory Reporting (think of line drawing). The path continued through a series of exercises in the creation of bold, exotic metaphors, which Hart called Double Images. He taught that these should be regarded as chords of objects and qualities, rather than as mere comparisons. Later, the student would work on the use of abstract language, of idea, for poetic effect, using a group of techniques that Hart summed up as Poetic Statement.

For Hart’s more ambitious students, this sequence was only the beginning. The goal was not the good line but the good poem, and the very strength of the parts could make it harder to build smoothly running wholes. A tempting fallback is always to insert some lines that demand less of (and offer less to) the reader. A kind of insulation or, as Kay Ryan has called it, “packing material.” Hart rejected this option, insisting that poems consist of “active” lines through out. It was like committing to a foreign language. “If you’re speaking French,” one student paraphrased him, “you have to speak French all the time.” These poem-level problems were the stuff of Hart’s advanced seminars. His students worked with poem plots, syntactical devices, gradations in intensity, narrative or associational structures. Some found themselves drawn to meter and rhyme, and exercises were found to strengthen formal muscles, too. Studying the results and the literary record, Hart gave names to a number of organizational devices, including those he called Connotation Line, Listing, Scene Control, and Variation Technique.