The Hart Circle

Over the decades, a changing circle of students and colleagues surrounded Lawrence Hart. For a period, they identified as a group or movement: the Activists. The name came from the principle that all lines in a poem be alive, surprising, “active.” Of course the label was treacherous. It was necessary to explain, over and over again, that a political stance was not implied.

The circle existed before any title. One of the first to arrive was Jeanne McGahey. McGahey, thirty-one years old and married to a Berkeley policeman, already had the beginnings of a career. She had appeared in 1936 in The New Republic. She was, however, dissatisfied with her poetic skills, feeling, as she said later, that she didn’t know where to go next.

McGahey liked to recount a story of her first glimpse of Hart. He was having an unusually hard time discouraging the use of worn-out cliches. “But, Mr. Hart,” the victim was saying, “the flowers were dancing.” Losing his classroom poise for once, Hart turned his back, slumped against the blackboard, and muttered, “Oh, my God.” McGahey was smitten. Joining the class, she seized on the techniques being taught as tools she could apply immediately in her work. LINK TO POEM

It was also in 1937 that Rosalie Moore began studying with Hart. Moore, who held a master’s degree in English from the University of California at Berkeley, had just quit a radio job to stake everything on a writing career. A member of the California Writers’ Club, she brought a whole contingent from the local chapter to the Hart class at the Technical High School in Oakland. Like McGahey, Moore felt doors opening. “I had had other creative classes or poetry appreciation courses,” she wrote much later, “but nobody before had given me a channel and a method that I could use so productively.” LINK TO POEM

Robert Horan was 13 years old when his mother, Carolyn, saw a newspaper item about the Oakland classes and started bringing her son. A youngster of obvious brilliance and great charm, Horan was reportedly one of the subjects of a study designed to follow the progress of children with very high IQs. He took to the disciplines Hart offered with extraordinary speed. LINK TO POEM

By 1938 these writers were meeting with Hart in private. At this stage he did not collect tuition. Rather, a bargain was struck. The members of the early group agreed that, as they gained recognition (an outcome that none doubted), they would use their stature to promote one another and Hart himself. They would, in short, provide him the prestige, the platform, that he otherwise completely lacked. This intrinsically unstable arrangement seems to have worked for a number of years.

Ideas of Order

In 1945, George Leite, publisher of the Berkeley magazine Circle, invited Hart and his colleagues to produce statements of theory and practice. The result was a feature (and offprint) called Ideas of Order in Experimental Poetry; this is sometimes regarded as an Activist manifesto. Hart’s contribution, “Some Elements of Active Poetry,” developed ideas from Benedetto Croce’s Aesthetics. Esthetic or connotative meaning, said Croce, should not be considered a mere adornment of literal or denotative meaning but rather must be recognized as, so to speak, a co-equal branch. “Ascience of intuitive knowledge,” wrote Croce, “ is timidly and with difficulty admitted by but a few.” Hart’s life was devoted to advancing such a science.

The Activist heyday

At the midpoint of the century, after years of growing exposure, a breakthrough came. First Robert Horan and then Rosalie Moore were selected by W. H. Auden for inclusion in the Yale Younger Poets Series. The still-tentative Activist label was set in stone when Auden employed it in his introducing to the Moore volume, The Grasshopper’s Man and Other Poems.

In 1951, the editor of Poetry, Karl Shapiro, invited Hart to guest-edit an entire issue devoted to the group and its approaches. Addressing the work of 16 poets, Hart did not take the usual course of gushing: “The selection of poems in this issue of Poetry may seem very uneven, partly because of the sequence in which some of the poets are working out their technical problems.…In a sense they sometimes do stammer, but I think they stammer in poetry.”

The issue also includes a letter from William Carlos Williams, who had developed a fondness for some of the most adventurous Activist work. Later in 1951 Williams wrote of Moore: “It is shocking for the uninformed to look at a Picasso or to pick up a poem by Rosalie Moore. He can’t understand them. He will never understand them until he has CHANGED within himself.”

A counterrevolution

Near the end of the 1950s came another invitation from Poetry. Henry Rago, Shapiro’s successor as editor, asked Hart to guest-edit a feature titled “Activists: A Sequel.” This September 1958 issue provides a nice snapshot of the group twenty years after its beginnings, including much work by a younger generation.

Also included was an essay by Rosalie Moore, “The Beat and the Unbeat,” taking notice of a new force in American poetry. In Lawrence Hart’s home region, the transplanted New York Beats had fused with local tendencies in what was called “the San Francisco Renaissance.” Since the 1956 publication of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, the phenomenon had captured national attention. Hart found himself and his colleagues unwelcome in the new constellation. He also saw little merit in the trumpeted works, finding in them pure laziness or at best a recycling of old Surrealist experiments.

As the movement nonetheless gained ground, Hart sought to set a backfire. In June 1959, he wrote to San Francisco Chronicle book reviewer William Hogan with a call for “a movement to recredit poetry in San Francisco after the Beat Generation fever.” Hogan sent the letter for comment to Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg’s publisher; Ferlinghetti returned it with mocking annotations in a Dada vein. Jeanne McGahey, in turn, wrote a satirical poem aimed at Ferlinghetti. Hogan printed parts of this exchange and following letters, but there was limited sequel.

It was soon apparent that the group was facing not a regional but a national—and soon international—change of mood. A reaction against Modernist demands and practices, building for some time, had taken hold on both U.S. coasts (Kenneth Koch’s “Fresh Air” appeared at almost the same moment as “Howl”) and at other centers like Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Once begun, the change of climate was astonishingly rapid. When Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry appeared in 1960, collecting “215 poems culled from the most authentic and interesting poetic voices to emerge in the past fifteen years,” the Activists were conspicuous by their absence. Though Moore and McGahey continued to appear in leading magazines through the mid-1960s, the weather had definitely changed.

From group to Institute

Now and then the fog would life. In 1962, Hart published the collection Accent on Barlow, a small anthology centered on the rather romantic figure of Robert Barlow, a noted anthropologist, associate of H. P. Lovecraft, and sometime Activist poet. LINK TO POEM It is now something of a cult classic. In the 1970s, current or former Hart students had volumes with Woolmer-Brotherson, a small but respected New York house led by a former Hart associate. John Hart’s The Climbers appeared with the Pitt Poetry Series in 1978.

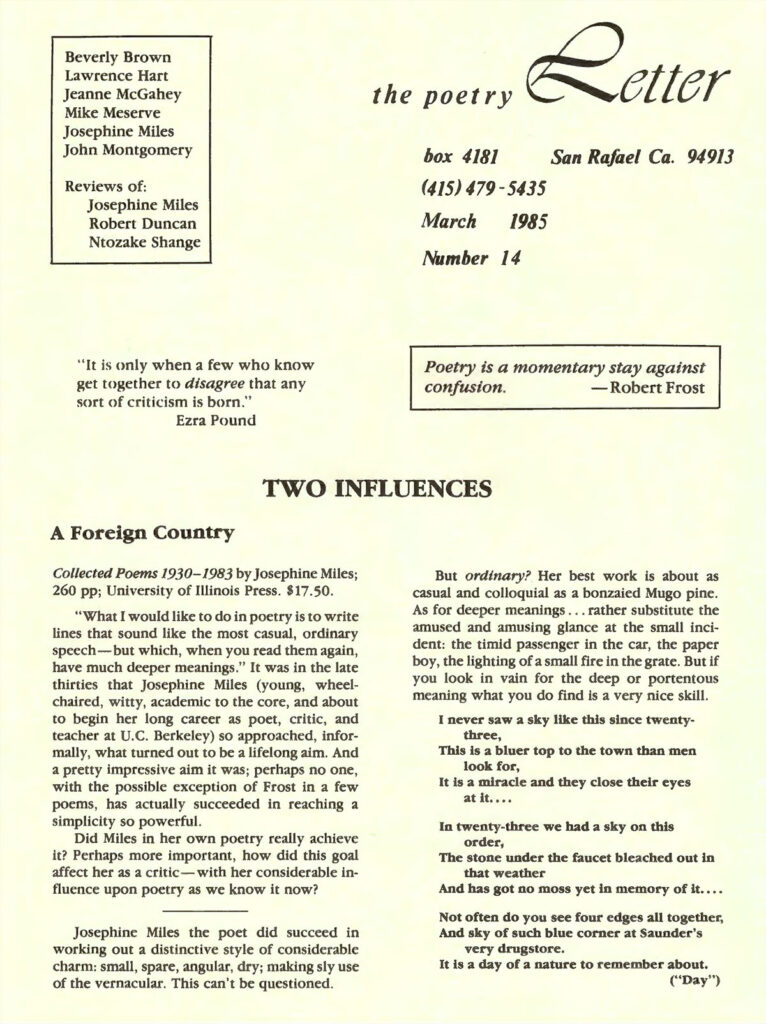

Then there was the poetry LETTER. McGahey served for years as screen reader for the Phelan and Jackson literary awards given by the San Francisco Foundation. In 1983, her contacts led to grant support for a newsletter of literary debate. Distributed free throughout Northern California, the poetry LETTER ran from 1983 to 1986 and did not disappoint in drawing controversy. It was at this point that the hitherto loose group crystallized as a non-profit organization, the Lawrence Hart Institute.

A final significant recognition of the original Activists came in 1989, when McGahey’s Homecoming with Reflections appeared in the Quarterly Review of Literature series at Princeton.

Into the new century, poets have continued to work in the seminar and show the influence of Activist ideas. Notable was Fred Ostrander, whose connection goes back to the 1950s. In 2009, his second collection, Petroglyphs, was selected for publication by San Francisco’s Blue Light Press. His New & Collected, It Lasts a Moment, would follow in 2013 with Sugartown Publishing, a San Francisco Bay Area house. LINK TO POEM

Sugartown also issued titles by John Hart, Patricia Nelson, Bonnie Thomas, and Judith Yamamoto, each with an introduction by Hart. Nelson, the most prominent of the circle in this century, would follow with four additional books; the latest is Monster Monologues with Fernwood Press (2025).

Robert Barlow: The Gods in the Patio; To One Rescued

Waltrina Furlong: Nor I

J. Hart: The Faller

L. Hart: Sonnet III

Robert Horan: Litany; Antiphonal Song

Jeanne McGahey: Warning by Daylight; Homecoming with Reflections

Mike Meserve: Geraniums

Jon Miller: On Receiving Notice of My Divorce in the Mail

Rosalie Moore: Shipwreck; The Mind’s Disguise

Patricia Nelson: Noah Waits

Fred Ostrander: The Deluge; The Station 3

Estelle Solomon: Words

Bonnie Thomas: September’s Pause

Judith Yamamoto: Stari Most